A complete breakdown of the private equity fund structure. Learn how GPs, LPs, fees, and carried interest work together in the world of PE investments.

At its most fundamental level, a private equity fund structure is a purpose-built legal and financial vehicle. Its entire reason for being is to pool money from investors, use that capital to buy and improve private companies, and eventually sell them for a handsome profit. This structure is the very bedrock that defines the relationship between the fund managers and the investors who put up the cash. It governs everything—how money moves, who makes the big decisions, and how the spoils are divided.

It helps to think of a private equity fund structure like the architectural plan for a high-stakes building project.

The General Partner (GP) is the master architect and the general contractor rolled into one. They're the experts who draw up the investment strategy, source the properties (the companies), manage the intensive renovations (the operational improvements), and orchestrate the final sale. On the other side, you have the Limited Partners (LPs). They are the clients financing the whole endeavor, providing the capital but trusting the architect to manage the complex, day-to-day work.

This setup isn't just for show; it serves a few critical purposes:

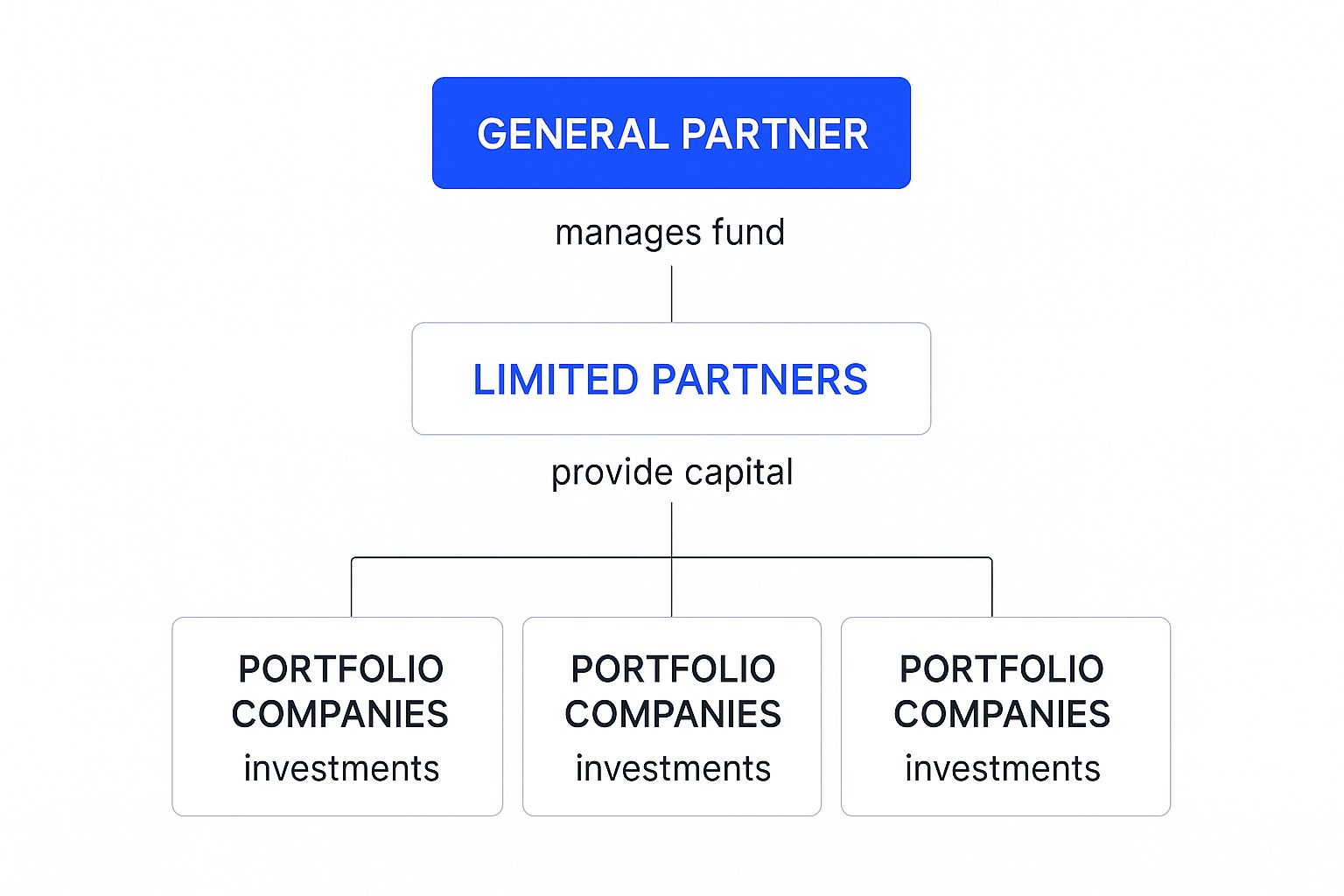

The diagram below really clarifies this core hierarchy. It shows how the GP takes capital from the LPs and directs it into a portfolio of different companies.

This visual makes it easy to see the flow of capital and command. The GP sits at the top, calling the shots on behalf of the LPs, who provide the financial fuel for all the investments.

No matter the specific investment strategy—whether it's buyouts, growth equity, or venture capital—every private equity fund is built from a few core, non-negotiable parts. These pieces work in concert to create a legally sound and effective investment machine. Getting a handle on them is the first real step to understanding how the whole ecosystem operates.

The real genius of the private equity fund structure is its clean separation of duties. It gives capital providers (LPs) a ticket to potentially high-return investments without requiring them to have the deep, specialized operational skills that the fund managers (GPs) bring to the table.

To make this even clearer, here’s a quick summary of the essential players and documents you'll find in almost any fund.

| Component | Role/Purpose | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|

| General Partner (GP) | The fund management firm making all investment decisions. | To find, buy, manage, and sell portfolio companies to generate strong returns. |

| Limited Partners (LPs) | Institutional or individual investors who provide the capital. | To earn passive returns on their capital with clearly limited personal risk. |

| Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA) | The legal contract governing the fund's terms, fees, and rules. | To create a clear, legally-binding rulebook for the GP-LP relationship. |

| Portfolio Companies | The private businesses that the fund acquires and actively manages. | To be improved operationally and financially, setting them up for a profitable sale. |

This foundational structure provides the clarity and legal protection needed to manage billions of dollars effectively, forming the basis for the entire private equity industry.

At the heart of any private equity fund is a critical partnership between two key players: the General Partner (GP) and the Limited Partners (LPs). How these two groups interact, what they're responsible for, and where their interests align (and sometimes diverge) defines the entire structure. Getting this relationship right is what makes or breaks a fund.

You can think of it like a high-stakes expedition. The GP is the experienced expedition leader—the one who knows the terrain, picks the route, and makes the critical decisions on the ground. The LPs are the wealthy patrons who finance the entire journey. They trust the leader's expertise to bring back a treasure far greater than their initial investment.

The General Partner is the private equity firm itself—the team on the front lines making all the key decisions. This isn't a passive, sit-back-and-watch role. It's a demanding, hands-on job that covers the entire investment lifecycle, from start to finish.

The GP's core responsibilities are extensive:

Here’s the catch: the GP assumes unlimited liability for the fund's debts and obligations. This structure is a powerful motivator. It ensures the GP has serious "skin in the game," aligning their interests directly with those of the LPs they serve.

The best GPs aren't just financial engineers; they're business builders. Their true value is often realized in their ability to step inside a company and fundamentally improve its operations, which is what separates the top-tier funds from the pack.

This entire process is governed by strict fiduciary duties. The GP is legally and ethically bound to act in the best interests of the LPs, a principle that underpins the trust essential to the private equity model.

The Limited Partners are the fuel that powers the private equity engine. These are the investors who provide the vast majority of the capital, typically 99% or more of the fund's total. LPs are almost always large institutional players—pension funds, university endowments, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds—or very high-net-worth individuals.

By design, their role is passive. LPs commit their capital and then step back, entrusting the GP to find, manage, and exit investments successfully. This passive arrangement comes with a crucial legal protection: limited liability.

An LP's risk is strictly capped at the amount of capital they've committed to the fund. If the fund's investments go south or it runs into legal trouble, an LP can't lose more than their initial stake. This protection is what makes it possible for institutions to allocate massive sums to private equity.

While they don't get involved in daily operations, LPs aren't completely powerless. They retain important oversight rights, such as receiving detailed quarterly performance reports and voting on major changes to the fund's strategy, which keeps the GP accountable.

If a private equity fund is the architectural blueprint, the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA) is the legally binding constitution. This is the single most important document in the entire fund structure. It’s a dense, often intimidating rulebook that lays out the entire relationship between the General Partner (GP) who manages the money, and the Limited Partners (LPs) who provide it.

Think of it as the ultimate pre-nup for a massive financial partnership. The LPA translates the GP's pitch deck promises into concrete, enforceable terms. It anticipates conflicts, clarifies who is responsible for what, and sets firm boundaries on what the GP can and can't do with the LPs' capital. A well-crafted LPA is the bedrock of trust, creating the alignment you need for a high-stakes, decade-long relationship to actually work.

While LPAs can easily stretch to hundreds of pages, the real action is concentrated in a few key clauses. These sections dictate the fund's timeline and the fundamental safeguards protecting investors. You don't need to be a lawyer, but you absolutely need to grasp these concepts to understand how a fund really operates.

Here are the terms that form the fund's operational skeleton:

These clauses create a predictable and accountable framework. For a deeper dive into these and other critical terms, you can read our comprehensive guide to key clauses in a Limited Partnership Agreement. Our guide breaks down the legal jargon into practical insights for GPs and LPs alike.

The LPA is where a fund's investment philosophy meets legal reality. It's the mechanism that ensures a GP's promises during fundraising are legally upheld throughout the entire life of the fund, protecting LPs from strategic drift and mismanagement.

Beyond just timelines, the LPA lays out the entire governance structure of the fund. It details the rights of LPs—like their power to remove a GP for serious misconduct (think fraud or gross negligence) or vote on major changes to the fund's strategy.

The LPA also establishes the Limited Partner Advisory Committee (LPAC). This is a small board of representatives from the fund's major LPs who act as a sounding board for the GP. They are typically called upon to review and approve potential conflicts of interest, like a deal where the GP might be on both sides of a transaction.

Ultimately, every single clause in the LPA is geared toward one thing: aligning the interests of the GP and the LPs. It’s about making sure everyone is rowing in the same direction. By setting clear expectations and providing a roadmap for resolving disputes, the LPA becomes the indispensable document that holds the entire private equity structure together.

At the heart of every private equity fund is a compensation structure that has stood the test of time: the "2 and 20" model. This isn't just industry jargon—it's the engine that powers the entire relationship between the fund managers, or General Partners (GPs), and their investors, the Limited Partners (LPs).

To really grasp how private equity works, you have to understand how the people running the show get paid. It all boils down to two key components: a management fee to keep the lights on and a performance fee that rewards hitting it out of the park.

The first piece of the puzzle is the management fee. This is an annual fee, historically 2% of the total money committed by investors, that the GP collects to run the fund. It's the "2" in the classic "2 and 20" setup.

Think of this fee not as profit, but as the fund’s operating budget. It’s what pays for the day-to-day costs of doing business, like:

This predictable income stream ensures the GP can focus on finding and growing great companies without worrying about short-term cash flow. It’s the stability that allows them to play the long game.

While the management fee keeps the fund running, carried interest—or "carry"—is what truly aligns everyone’s interests. This is the GP's share of the fund's profits, typically 20%, and it's the real prize.

Crucially, the GP doesn't see a dime of carry until after the investors get all their initial capital back, plus a pre-agreed minimum return. This performance-based model is the primary motivation for a GP to not just find good companies, but to make them great. Their biggest payday only happens if their investors win first.

Carried interest is the ultimate "skin in the game" mechanic. It fundamentally ties the GP's financial success to the success of their investors, transforming the relationship from a simple service provider to a true financial partner.

This is what makes private equity so different. The GP isn't just managing a portfolio; they are incentivized to roll up their sleeves and actively help businesses grow to maximize their value.

Before the GP can collect that 20% carry, they have to clear a couple of important hurdles. These are baked into the fund’s legal documents to protect investors and ensure profits are distributed fairly.

The broader economic climate also plays a huge role here. For example, according to analysis from PwC, to hit a 20% internal rate of return (IRR) over seven years when interest rates are at 7%, a firm needs to grow its portfolio companies' earnings by about 4.2% annually. If rates were just 3%, that required growth drops to only 1.7%. It just goes to show how much external factors can raise the bar for earning that carry.

For decades, the private equity world marched to the beat of a single drum: the 10-year, closed-end limited partnership. It was the industry standard, the bedrock of the asset class. But the market has grown up, and that one-size-fits-all approach just doesn't cut it anymore. Today's investors, from enormous institutions to nimble family offices, are pushing for more flexibility, greater transparency, and investment options that truly fit their specific goals.

In response, sharp General Partners (GPs) are getting creative. They're moving beyond the classic commingled fund, not just by tweaking a few terms here and there, but by fundamentally redesigning how capital is raised and put to work. This has led to a whole new ecosystem of fund vehicles built for the modern investor.

One of the most significant new structures on the block is the co-investment fund. The concept is simple but powerful. Instead of just putting money into a blind pool and hoping for the best, Limited Partners (LPs) get the chance to write a second, separate check to invest directly into specific deals they really like, right alongside the main fund.

It's a classic win-win situation.

Think of it as giving LPs a chance to move from the passenger seat up to the co-pilot's chair—they don't get the controls, but they have a much better view.

For the titans of the investing world—sovereign wealth funds, massive pension plans—even co-investments might not offer the level of control they're looking for. That’s where separately managed accounts (SMAs) enter the picture. An SMA is essentially a "fund of one," a bespoke vehicle created by a GP for a single, large-scale investor.

With an SMA, the investor can hammer out highly customized terms on everything from the fee structure and investment mandate to specific governance rights and reporting details. This kind of tailoring is attracting huge amounts of capital. In fact, GPs are increasingly sourcing capital through SMAs and co-investments, adding a multitrillion-dollar layer of assets that traditional fund metrics don't even capture. This shift is profoundly reshaping the global private markets.

The rise of SMAs and other alternative vehicles marks a critical change in the power balance between GPs and LPs. It's a move away from a standardized, take-it-or-leave-it product toward a more collaborative, service-focused relationship where the investor's unique objectives are front and center.

The biggest knock against the traditional PE fund has always been its illiquidity. Your capital is locked up for 10 years or more. To address this major pain point, evergreen funds have started to gain real traction. These are open-ended funds with no fixed end date, offering windows for investors to cash out their shares or for new investors to come in.

While you don't get the daily liquidity of a mutual fund, they offer a much-needed middle ground. This opens the door to private equity for wealth managers and high-net-worth individuals who need more flexibility than the old model could provide. Of course, the administration behind these varied structures is complex. Managing them effectively means mastering the back-office details. For a closer look, check out our detailed guide to private equity fund administration.

A major trend is reshaping the private equity world: a powerful flight to size and stability. With economic uncertainty and fluctuating interest rates creating choppy waters, Limited Partners (LPs) are increasingly steering their capital towards large, established mega-funds. This isn't just about chasing big names; it's a calculated move.

LPs see these larger private equity fund structures as a safer harbor. A mega-fund, often managing tens of billions of dollars, can build a hugely diversified portfolio that's less exposed to a downturn in any single industry or region. It's the difference between investing in a massive, professionally managed fleet versus a single ship. The fleet can easily weather a local storm that might sink a smaller vessel.

Beyond diversification, these large fund structures bring incredible operational resources to the table. They have deep benches of experienced partners, dedicated in-house teams for everything from digital transformation to supply chain logistics, and a global network that can open doors smaller firms can't even find.

For LPs, this all adds up to greater confidence. They're backing management teams with proven track records, often spanning decades of navigating complex market cycles. When the economic forecast is cloudy, the established brand and institutionalized processes of a mega-fund offer a level of assurance that's hard to pass up.

In uncertain times, capital flows toward perceived safety and predictability. The consolidation of capital into mega-funds reflects a market-wide bet that proven platforms, deep operational expertise, and portfolio diversification are the most reliable drivers of returns.

You can see this shift clearly in the fundraising data. We're seeing a fascinating trend where the total number of funds being raised is actually dropping, but the average fund size is shooting up. After the recent interest rate shocks, the average fund size jumped to $843 million—way above the historical five-year average. This figure highlights just how much investors prefer the perceived safety and proven track records of large, experienced PE firms. You can dig deeper into this trend in Bain & Company's insightful global report.

This consolidation of capital creates a more competitive, two-tiered landscape. As mega-funds soak up more capital, it puts immense pressure on smaller and emerging managers. They now have to compete for a shrinking slice of the pie, making it much harder for new players to break through without a truly unique strategy.

This new reality forces a critical choice for fund managers. To succeed, a firm must either:

Trying to occupy the middle ground is becoming a very tough proposition. This evolution in private equity fund structures is pushing the industry toward a model where you’re either a dominant, large-scale generalist or a hyper-focused, best-in-class specialist. The market is rewarding clarity and excellence, whether that comes from sheer size or surgical precision.

The private equity world has its own language and set of rules. As you get more familiar with how these funds operate, you're bound to have some questions. Let's walk through a few of the most common ones that come up.

A capital call is simply the formal process a General Partner (GP) uses to ask its investors for money. Think about it: when an LP commits $10 million to a fund, they don't just wire the full amount on day one. That would be incredibly inefficient.

Instead, the GP "calls" for portions of that committed capital as needed—for a new deal, to cover fund expenses, or to pay management fees. This "just-in-time" funding model is a huge benefit for Limited Partners (LPs), as it allows them to keep their money working in other investments until the GP has a concrete reason to put it to use.

An easy way to understand a capital call is to think of it like a general contractor building a house. The contractor doesn't ask for the entire project cost upfront. They bill you in phases as they hit milestones—pouring the foundation, framing the walls, and so on. Capital is deployed only when there's real work to be done.

Private equity funds aren't designed to last forever. Most have a fixed lifespan, typically around 10 years. As a fund nears the end of its term, the GP's focus completely flips from buying companies to selling them.

This final "exit" or "harvesting" period is all about liquidating the fund's remaining investments. The GP will look for the best way to sell each company, which usually happens in one of a few ways:

After every asset is sold, the final cash is paid out to the LPs based on the distribution waterfall laid out in the LPA. Once all the money is returned and the books are closed, the fund is officially dissolved.

At a high level, yes—both use the classic GP/LP partnership. But once you look under the hood, their different investment playbooks create some important structural differences.

Private equity funds are usually buying mature, stable companies. They often take a controlling stake and get their hands dirty improving operations. Venture Capital (VC) funds, on the other hand, are placing bets on high-growth, early-stage startups where they take a minority stake.

This massive difference in risk and strategy ripples through the fund's legal documents. The terms in their respective Limited Partnership Agreements—everything from fees to investor rights—are tailored specifically for their very different worlds.

Ready to move beyond spreadsheets and manage your fund like a top-tier firm? Fundpilot provides emerging managers with institutional-grade tools for LP reporting, pipeline management, and automated fund administration. See how we can help you scale your operations and impress your investors.