Choosing between an asset deal vs stock deal? Our guide unpacks the critical differences in tax, liability, and complexity for buyers and sellers.

When you're buying or selling a business, one of the first and most critical decisions you'll face is the deal structure: will it be an asset deal or a stock deal? This isn't just a technicality; it’s a foundational choice with huge ripple effects on everything from taxes to legal liabilities.

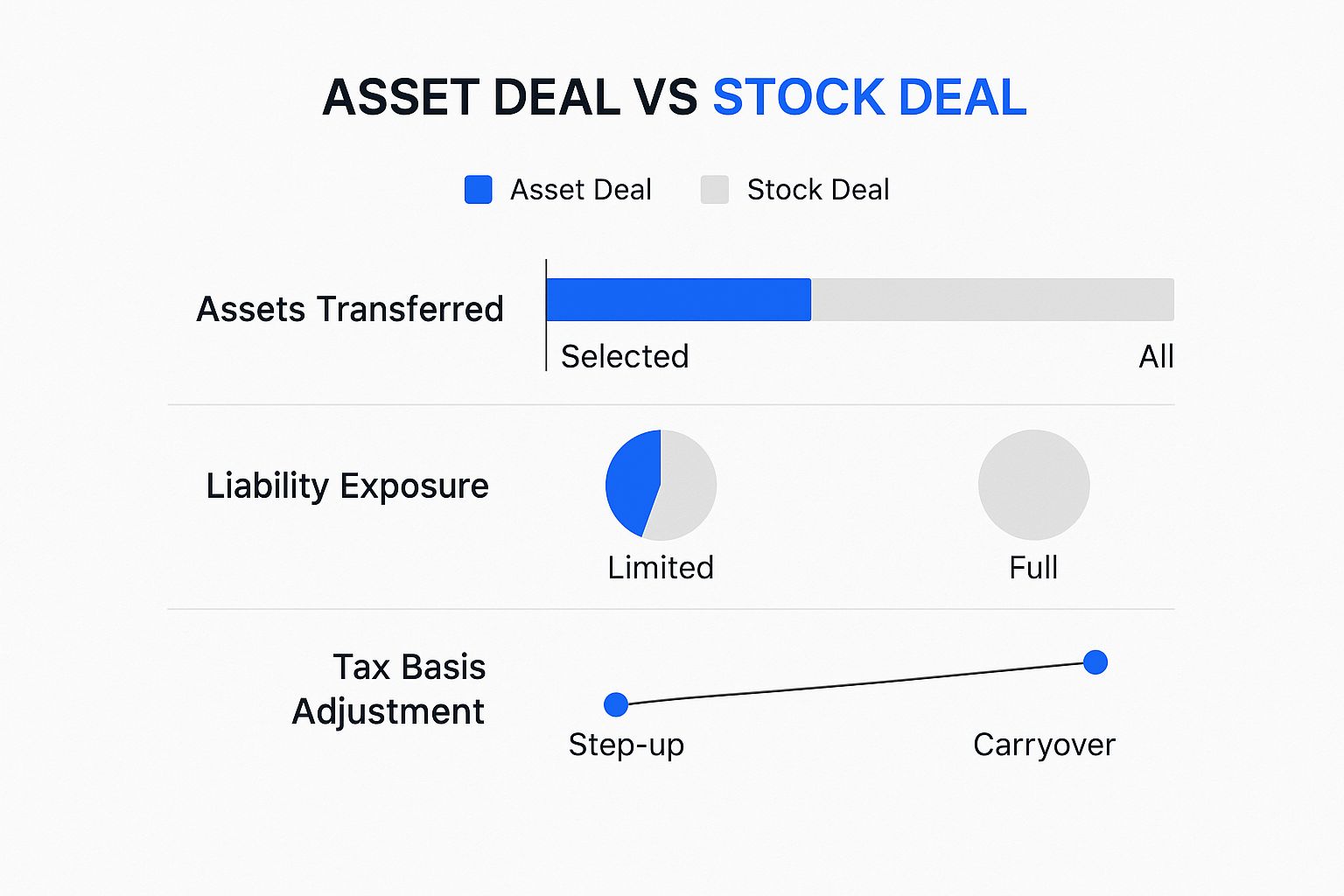

In an asset deal, the buyer purchases specific assets and assumes only certain liabilities from the seller's company. Think of it as a custom shopping trip. In a stock deal, the buyer acquires the entire company—all its shares, assets, and, crucially, all its liabilities, both the ones you know about and the ones you don't.

This initial choice between an asset deal and a stock deal will fundamentally shape the transaction's tax implications, risk exposure, and even how smoothly the business continues to operate post-acquisition. It’s a strategic decision that defines the financial and legal future for both sides of the table.

Buyers almost always lean towards an asset deal. Why? It gives them the power to cherry-pick the good stuff—equipment, intellectual property, key contracts, customer lists—while leaving behind any unwanted liabilities with the seller. The other major win for the buyer is a tax advantage called a "stepped-up basis." This allows them to re-value the purchased assets at their current fair market price and depreciate them from that higher value, creating a nice tax shield for years to come.

Sellers, not surprisingly, usually push for a stock deal. It's a much cleaner break. They sell the entire company in one fell swoop and walk away. The real prize for the seller, though, is the tax treatment. Gains are typically taxed just once at the lower long-term capital gains rate. This helps them avoid the dreaded "double taxation" that can hit C-corporations in an asset sale, where the corporation is taxed on the sale and shareholders are taxed again on the distribution.

The image below gives a great visual breakdown of how assets, liabilities, and the tax basis are treated in each scenario.

Ultimately, it comes down to a classic trade-off: buyers want the control and tax benefits of an asset deal, while sellers prefer the simplicity and tax efficiency of a stock deal.

Interestingly, the size of the business being sold often steers the decision. While stock sales account for about 30% of all deals, they are overwhelmingly the preferred method for larger companies. For a big, complex organization, transferring the entire legal entity is just simpler and preserves critical contracts, licenses, and permits that might be a nightmare to reassign individually.

On the flip side, smaller businesses are far more likely to transact through an asset deal. Here, buyers are more focused on de-risking the purchase by sidestepping any potential hidden skeletons in the closet. Navigating these nuances is exactly why a deep understanding of the legal aspects of M&A is so important.

For a quick reference, here’s a high-level summary of the key differences between the two deal structures.

This table lays out the fundamental distinctions at a glance.

| Attribute | Asset Deal | Stock Deal |

|---|---|---|

| What's Transferred | Only specific, pre-selected assets and liabilities. | All company shares, which includes every asset and liability. |

| Liability Exposure | The buyer only takes on the liabilities they explicitly agree to. | The buyer inherits every liability, even unknown or future ones. |

| Tax Basis | The buyer gets a "stepped-up" basis on assets for new depreciation. | The buyer inherits the seller's existing tax basis (carryover basis). |

| Contract Continuity | Contracts, permits, and licenses often need to be reassigned or renegotiated. | Contracts, permits, and licenses typically stay with the company entity. |

While this table offers a solid overview, the best path forward always depends on the specific circumstances of the deal and the goals of each party involved.

For a buyer, the decision between an asset and a stock deal often boils down to one critical question: how much risk are you willing to take on? The way each structure handles liabilities creates a night-and-day difference, fundamentally shaping the safety and appeal of the transaction.

In an asset deal, the buyer is in the driver's seat. You get to be incredibly selective.

This structure allows you to "cherry-pick" the good stuff—machinery, intellectual property, key customer contracts—while intentionally leaving the bad stuff behind. All those unwanted or unknown risks, like old legal squabbles, lingering tax problems, or potential employee lawsuits, stay with the seller. It's a powerful defensive move.

A stock deal is the polar opposite. Here, you're buying the entire company, warts and all. The legal entity transfers to you completely, bringing its entire history—every known, unknown, and potential liability—along for the ride.

The contrast here isn't subtle. With an asset deal, the purchase agreement is your shield. It explicitly lists every single asset and liability you're acquiring. If it's not on that list, it’s not your problem.

Now, flip to a stock deal. You inherit the entire corporate shell. Imagine closing the deal and then discovering a massive, undisclosed environmental cleanup liability from a decade ago. In a stock purchase, that multi-million dollar headache is now yours. This is precisely why a grueling, no-stone-unturned due diligence process is absolutely non-negotiable in stock deals.

An asset deal is surgical; it lets a buyer carve out the valuable parts and build a wall around risk. A stock deal is an all-or-nothing bet where you inherit the company's complete history—past, present, and future.

The operational fallout from these differences is huge. In an asset deal, you're buying individual pieces, which means you have to go through the often tedious process of transferring each one. This can involve getting third-party approvals for contracts, retitling assets, and a lot of paperwork that can easily add months to the closing timeline.

But that complexity is the price you pay for control.

A stock deal, on the other hand, is much cleaner administratively. The business continues to run under new ownership without much disruption because the corporate entity itself never changed. That simplicity, however, comes at the steep cost of inheriting every potential skeleton in the closet, from old lawsuits to hidden tax issues. This trade-off is often the central point of negotiation and a key driver behind why one structure is chosen over the other. You can learn more about these distinctions in M&A transactions to see how they play out in the real world.

When you get down to the brass tacks of structuring a deal, nothing gets debated more fiercely than the tax implications. It’s where the financial outcomes for both the buyer and seller split dramatically, making it a pivotal point in any negotiation.

For buyers, the big prize in an asset deal is the "stepped-up basis" on the purchased assets. This is a huge win. It means the assets are revalued to their current market price right at the time of sale. This new, higher basis gives the buyer a powerful tool for future tax savings, allowing them to depreciate or amortize the assets and reduce their taxable income for years to come.

A stock deal offers nothing of the sort. The buyer simply inherits the company's old, historical asset basis—a "carryover basis." This means missing out on the chance to generate those new depreciation shields, which can have a real, tangible impact on the company's cash flow after the acquisition.

While buyers love the stepped-up basis in an asset deal, sellers of C-corporations see it as a financial nightmare. Why? Because it often triggers the dreaded double taxation.

First, the corporation itself pays taxes on the gains from selling its assets. Then, when the cash that’s left over is paid out to the shareholders, they get taxed again at their individual level. It's a painful one-two punch to their net proceeds.

This is exactly why sellers almost always push for a stock deal. The sale of stock typically creates a single, much cleaner tax event. The gain is usually taxed just once at the long-term capital gains rate, which is far more favorable than ordinary income rates. For sellers focused on walking away with the most money, it's the clear winner.

When it comes to the asset deal vs. stock deal debate, the tax treatment creates an inherent tug-of-war. What directly benefits the buyer often directly penalizes the seller, and vice versa.

To give you a clearer picture, let's break down how the tax treatment differs for each party in both scenarios.

| Tax Aspect | Buyer Perspective (Asset Deal) | Seller Perspective (Asset Deal) | Buyer Perspective (Stock Deal) | Seller Perspective (Stock Deal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asset Basis | Gets a stepped-up basis to fair market value. | Not a direct concern for the seller's entity. | Inherits a carryover basis (historical cost). | Not a direct concern for the shareholder. |

| Depreciation/Amortization | Can depreciate/amortize assets from the new, higher basis, creating tax shields. | N/A | Limited to the target's existing depreciation schedule. | N/A |

| Tax Rate | N/A | Faces potential double taxation (corporate level on asset sale, then shareholder level on distribution). | N/A | Typically pays tax once at the lower long-term capital gains rate. |

| Goodwill | Can amortize purchased goodwill over 15 years. | N/A | Cannot amortize existing goodwill. | N/A |

This table really highlights the core conflict. Buyers get significant, long-term tax advantages from an asset deal, while sellers can protect their proceeds much more effectively in a stock deal.

The handling of Net Operating Losses (NOLs) adds another layer of complexity. These are valuable tax assets that can offset future profits, and who gets to keep them is a big deal.

But there's a huge catch. The ability to actually use these inherited NOLs is often severely limited by IRS Section 382, which kicks in after a significant ownership change. These rules can drastically reduce the value of the NOLs you thought you were acquiring.

The tax implications between these two structures are profoundly different. While buyers in asset deals get a 'stepped-up basis,' they lose out on NOLs. The complexities around NOL utilization rules impact M&A deals and require careful financial modeling to truly understand their value. The specific legal and financial frameworks governing these transactions are often spelled out in a company's terms and conditions, making it essential to do your homework before banking on any inherited tax benefits.

Beyond the balance sheets and tax implications, the path to closing a deal looks completely different depending on whether you choose an asset or a stock purchase. The deal structure you pick directly impacts the administrative burden, the consents you'll need from outsiders, and frankly, how smoothly the whole transition will go.

An asset deal might look great from a liability standpoint, but it's often an operational marathon. You're not just buying a company; you're meticulously transferring ownership of every single asset, piece by piece. It's a whole lot more involved than just signing over some stock certificates.

Think of an asset deal as deconstructing a business and putting it back together under a new roof. The buyer and seller have to create an exhaustive list of every asset and liability changing hands.

This means you'll be busy with:

This last point can become a major sticking point. Let's say the target company has a fantastic, below-market lease or a non-negotiable supply contract. If the landlord or supplier says "no" to the assignment, the buyer could lose a huge piece of the business's value. That refusal could even derail the entire deal. Getting these consents often takes a lot of time, careful negotiation, and sometimes extra cash, adding serious complexity and risk to the transaction.

The operational burden of an asset deal is its greatest weakness. The need to individually transfer titles, renegotiate contracts, and secure third-party consents can transform a straightforward acquisition into a prolonged administrative battle.

A stock deal, on the other hand, is a study in operational elegance. Since the buyer is just purchasing the entire legal entity, the business itself doesn't technically change—it just gets a new owner.

Everything stays in place. All the existing contracts, permits, licenses, and even employee relationships remain completely undisturbed. The company's legal name, its tax ID, and its agreements with customers and vendors all continue without a hiccup. You can forget about retitling assets or begging for contract assignments because the entity holding them remains the same.

This built-in continuity is a massive advantage. It makes for a much faster and less disruptive closing process. Ultimately, the decision often boils down to a critical trade-off. A buyer has to weigh the clean liability break of an asset deal against the speed and seamless transition of a stock deal. How tangled the company's contracts are can often be the factor that tips the scales.

Enough with the theory—let's get practical. The choice between an asset deal and a stock deal isn't an academic exercise; it's driven entirely by your specific circumstances. You won't find the perfect answer in a textbook. Instead, the right path emerges when you dig into the unique goals, risks, and characteristics of the business you're dealing with.

The best way to figure this out is to look at real-world scenarios. By walking through a few distinct situations, you’ll see how the pros of one structure become absolutely essential, while the cons of the other become total deal-breakers.

Picture this: you’re looking to acquire a company with a messy legal history. Maybe they have a trail of old employee lawsuits or a looming environmental problem. In a case like this, an asset deal isn't just a good idea—it's a move for self-preservation.

This structure lets you act like a surgeon, carefully selecting only the clean, valuable assets you want—things like equipment, customer lists, and intellectual property. You can intentionally leave behind all the known (and, more importantly, the unknown) liabilities with the seller's company. The asset deal creates a legal firewall, shielding your new investment from the seller's past mistakes. Trying to buy the same company via a stock deal would mean inheriting every single one of those headaches, a risk most buyers simply won't touch.

Here's another scenario where an asset deal shines: when a buyer is laser-focused on future tax benefits. The ability to get a stepped-up basis on the newly acquired assets is a massive financial advantage. It means the buyer can start depreciating the assets all over again from their new, higher market value. This generates significant tax shields that boost cash flow for years to come. If you're a buyer playing the long game of financial optimization, pushing for an asset deal should be a top priority.

The decision often comes down to a simple trade-off: Is your priority isolating yourself from the seller's history or preserving the seller's operational continuity? Answering that question will point you to the right starting point for negotiations.

Now, let's flip the script. Imagine the company you want to buy holds crucial non-transferable licenses, government permits, or major customer contracts. These are often tied directly to the legal entity itself and can't be reassigned without a mountain of paperwork—if they can be reassigned at all.

Trying to move these through an asset deal would be an administrative nightmare. It might even be impossible, potentially wiping out the very value you’re trying to acquire. In this situation, a stock deal is really the only way forward. By purchasing the entire company, stock and all, you ensure these critical licenses and contracts remain perfectly intact. The business just has a new owner. This operational continuity is the stock deal's greatest strength, making it the go-to choice when key agreements can't be disturbed.

From the seller's side of the table, a stock deal is almost always the preferred option, especially for C-corporations. The reason is simple: it avoids the brutal sting of double taxation. In an asset deal, the corporation pays tax on the sale proceeds, and then shareholders get taxed again when the money is distributed to them. A stock sale, on the other hand, typically creates a single, much cleaner tax event at the more favorable long-term capital gains rate, letting the seller keep a much bigger piece of the pie.

The tug-of-war between an asset deal and a stock deal can feel like an all-or-nothing choice, but it rarely is. In practice, seasoned negotiators know how to find a middle ground by blending elements of both, creating hybrid structures that get a deal across the finish line.

One of the most effective tools in the M&A playbook is the IRC Section 338(h)(10) election. This is a clever tax mechanism that lets a deal legally structured as a stock sale be treated as an asset sale for tax purposes.

Think of it as the best of both worlds. The buyer gets the highly desirable stepped-up basis in the assets, which means bigger depreciation write-offs down the road. At the same time, the seller gets the cleaner, simpler execution of a stock transfer. It’s a powerful compromise that can salvage a negotiation when tax treatment is the main sticking point.

Beyond specific tax elections, other creative solutions can help balance the scales. These negotiating tools are all about reallocating risk and value to make the final agreement more appealing to everyone involved.

A successful deal isn't always about one side winning. It's about finding a creative structure where both parties feel their primary needs—whether tax efficiency, risk mitigation, or operational continuity—have been met.

These strategies turn the rigid asset deal vs stock deal choice into a flexible negotiation. It’s about building a bespoke agreement that addresses the unique priorities of the buyer and seller. Of course, managing risk goes beyond the deal structure itself. Understanding compliance obligations is critical, and you can learn more about what GDPR means for your business in our detailed guide.

When you get down to the brass tacks of an asset deal vs a stock deal, a few key questions always pop up. Let's break down the answers to the ones I hear most often from both sides of the table.

Nine times out of ten, a seller is going to push for a stock deal. The reasoning is pretty straightforward: it’s cleaner and usually much better for them on taxes.

With a stock deal, the seller typically gets taxed just once at the long-term capital gains rate, which is a significant advantage. It also means they walk away completely, handing over the entire company—liabilities and all—to the buyer. No need to deal with the headache of dissolving what's left of the business afterward.

Yes, and this is one of the biggest draws of an asset deal. Its flexibility is a major plus for buyers. You can cherry-pick exactly what you want to acquire, whether it's just the customer contracts, a patent, or a specific piece of machinery.

This kind of surgical acquisition is perfect when a buyer only wants to absorb a specific product line or a strategic technology without taking on the entire corporate entity.

A stock deal transfers the entire history of the company to the buyer. In contrast, an asset deal allows the buyer to start with a clean slate, leaving the seller's historical baggage behind. This fundamental difference in risk transfer is often the central point of negotiation.

This is a critical point that requires careful handling. In a stock deal, the company itself doesn't change—only the owner does. For employees, it's usually business as usual, as their employment contracts simply transfer to the new ownership.

An asset deal is a different story. The seller technically terminates all employees, and the buyer then has the option to rehire them under new employment offers. This process needs to be managed carefully with HR to ensure a smooth transition for the people you want to keep.

Ready to move beyond spreadsheets and manage your fund like an institutional player? Fundpilot provides the reporting, administration, and analytics tools you need to impress LPs and scale your operations. See how we can help you grow by visiting https://www.fundpilot.app.