Discover how to master the valuation of private company assets. This guide explains key methods, challenges, and best practices for accurate business valuation.

Figuring out what a private company is worth isn't as simple as checking a stock ticker. It’s a delicate process, blending hard numbers with educated judgment to land on a value that everyone can stand behind. This number is more than just a figure on a page; it’s fundamental for everything from raising money to planning the company's future.

Think of valuing a private company like appraising a one-of-a-kind painting. There’s no daily market to tell you its exact price. For public giants like Apple or Microsoft, millions of trades on stock exchanges set a clear, real-time market value. A quick search gives you their share price, no debate needed.

Private companies, on the other hand, don't have this luxury. Their shares aren't traded openly, creating a big challenge: there is no single, objective price tag. Instead, their value has to be carefully pieced together using a combination of financial analysis, deep market knowledge, and some well-reasoned assumptions.

This is why we say it's part art, part science. You need the solid, quantitative "science" of financial modeling, but you also need the "art" of interpretation—understanding the story behind the numbers.

Getting to that final valuation isn't just a box-ticking exercise. It's a strategic pillar that influences almost every major decision a private business will make. The valuation sets the stage for a wide range of critical activities and conversations.

A company's valuation is often required at key inflection points in its lifecycle. The table below outlines some of the most common scenarios that trigger the need for a formal valuation.

| Scenario | Primary Reason for Valuation | Key Stakeholders Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Raising Capital | To determine the price per share for new investors and calculate ownership dilution. | Founders, Existing Investors, New Investors (VCs, Angels) |

| Mergers & Acquisitions | To establish a baseline for negotiating the sale or merger price. | Founders, Board of Directors, Acquiring Company |

| Employee Stock Options | To set a fair and legally compliant strike price for employee stock options (409A valuation). | Company Leadership, Employees, IRS, Auditors |

| Strategic Planning | To measure progress, identify value drivers, and inform long-term business strategy. | C-Suite, Board of Directors, Department Heads |

| Shareholder Buyouts | To determine a fair price for buying out a founder or major shareholder. | Departing Shareholder, Remaining Shareholders, Board |

Each of these moments hinges on having a credible and defensible valuation. It’s not just about reaching a final number, but about the integrity of the process behind it.

A strong valuation is defined not just by the final number, but by a transparent, robust, and well-supported process. It must be defensible under scrutiny from investors, auditors, and regulatory bodies.

The importance of this field is undeniable. The global market for private company valuation services hit $5.8 billion in 2023 and is expected to reach $9.7 billion by 2031. This growth is driven by a surge in M&A deals and the need for more sophisticated valuation methods that go beyond historical data. You can explore the full market analysis on private company valuation to see these trends in more detail.

Because there's no direct market price, a structured approach is absolutely essential. The entire process relies on established methodologies—which we'll dive into next—to build a logical and credible case for a company's worth. This blend of quantitative data and qualitative judgment is precisely why the valuation of a private company is such a unique challenge.

So, how do you actually put a number on a private company? It’s not about finding a single magic formula. Instead, valuators use a toolkit of proven frameworks, each looking at the business from a completely different angle.

Think of it like a team of art experts appraising a painting. One might analyze the artist’s historical significance, another will assess the physical condition of the canvas, and a third will compare it to recent auction prices for similar works. All of these viewpoints are essential to land on a credible value.

For the valuation of a private company, the three core methodologies are the Income Approach, the Market Approach, and the Asset-Based Approach. The strongest, most defensible valuations almost always come from a blend of these methods, not just relying on one.

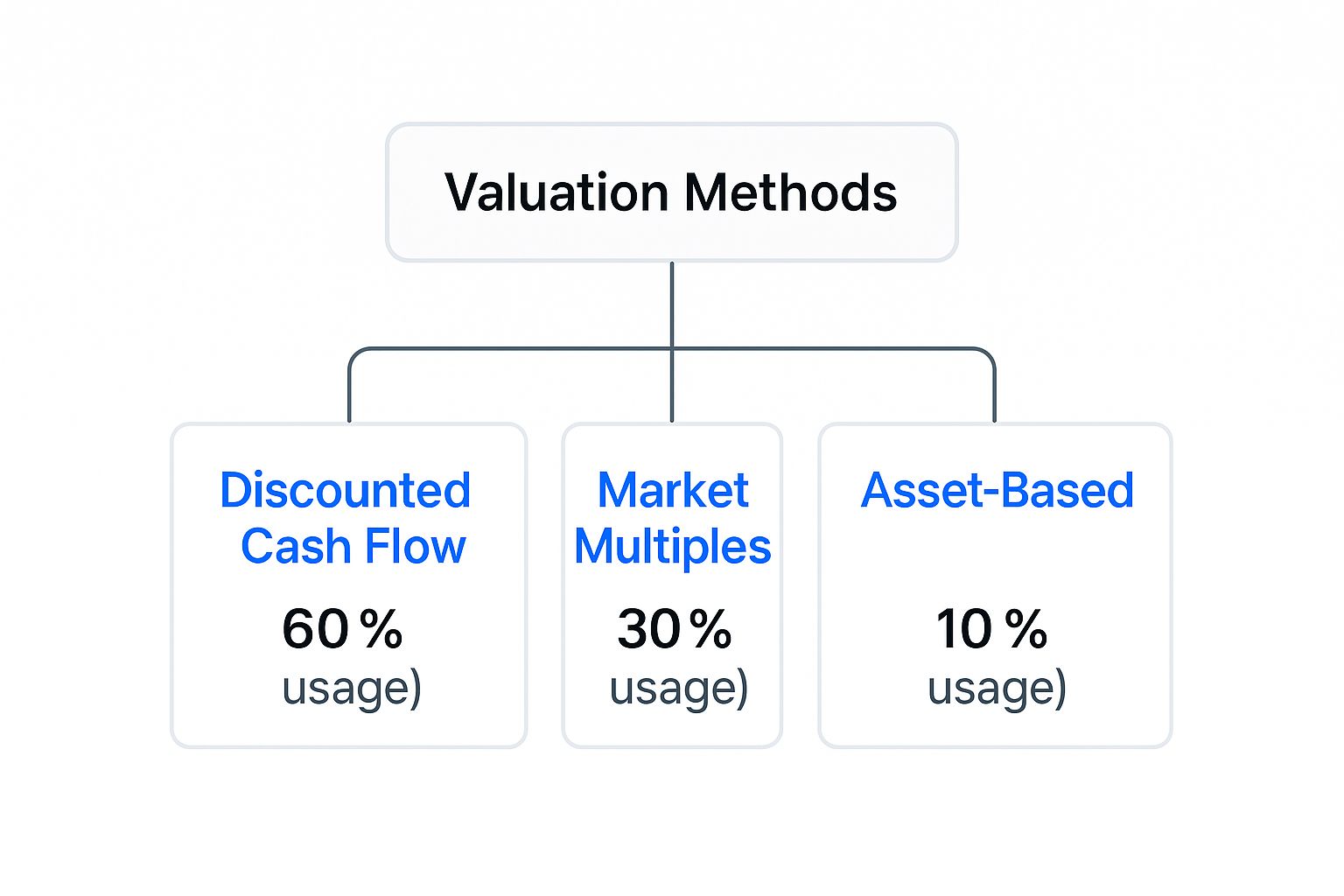

This infographic gives you a quick look at how often these methods are actually used in the real world.

As you can see, the Income Approach—especially the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model—is the go-to for most analysts. The Asset-Based approach, on the other hand, is used far more selectively.

The Income Approach is all about looking forward. Its entire premise is built on a simple idea: a business is worth the cash it’s expected to generate over its lifetime. The gold standard for this is the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis.

Let’s say you’re buying a popular local brewery. You aren't just paying for the brewing tanks and the current inventory of kegs. You're really buying its future profits—every pint, every flight, and every pretzel it will sell for years to come.

A DCF analysis quantifies this by:

This method is a favorite for both stable, cash-producing businesses and high-growth startups because it gets to the heart of economic potential, not just what a company owns right now.

The Market Approach is essentially a reality check based on what’s happening in the real world. It pegs a company’s value by comparing it to similar businesses that have recently been sold or are publicly traded. It’s the same logic you’d use to price your house—you look at what comparable homes in your neighborhood have sold for.

This method runs on valuation multiples. These are financial ratios like EV/EBITDA (Enterprise Value to Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) or, for many tech companies, a revenue multiple.

For instance, if other software-as-a-service (SaaS) companies with a similar profile are trading on the public market for an average of 7.0x their annual revenue, you can apply that same multiple to your company's revenue to get a ballpark valuation.

The Market Approach anchors your valuation in tangible, real-world transactions and current investor sentiment. It provides a powerful answer to the question, "What is the market actually willing to pay for a business like mine right now?"

The biggest hurdle here? Finding truly comparable companies. This is especially tough for businesses in niche industries. No two companies are perfect clones, so smart adjustments are always part of the process.

The Asset-Based Approach, sometimes called the cost approach, values a company by adding up all of its assets and subtracting its liabilities. It answers the fundamental question: "If we had to build this business from scratch, what would it cost?" The final number is the company’s Net Asset Value (NAV).

Think of this as a "liquidation" or "break-up" value. If a manufacturing firm went out of business, you'd sell off its factory, machinery, and inventory. The cash left over after paying all its debts is its asset-based value.

This approach is most useful for:

Its glaring weakness is that it completely ignores a company's most valuable intangible assets—things like brand reputation, proprietary technology, or a brilliant team. These are often the very things that drive success.

To make sense of it all, it helps to see these methods side-by-side. Each has its place, and the right one—or right mix—boils down to the specific company, its industry, and why the valuation is being done in the first place.

This table breaks down the core principles, best uses, and key challenges of each approach.

| Methodology | Core Principle | Best Suited For | Main Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income Approach | A company's value is the present value of its future cash flows. | Mature, stable businesses with predictable earnings and high-growth companies. | Highly sensitive to assumptions about future growth and discount rates. |

| Market Approach | A company's value is determined by what similar companies are worth. | Businesses in industries with many public companies or frequent M&A activity. | Finding truly comparable companies and making appropriate adjustments. |

| Asset-Based Approach | A company's value is the sum of its net assets. | Asset-heavy industries (e.g., real estate, manufacturing) or liquidation scenarios. | Fails to capture the value of intangible assets like brand or goodwill. |

At the end of the day, a credible valuation of a private company is rarely a single number pulled from one method. Experienced analysts triangulate—using multiple approaches to arrive at a valuation range. This gives a much more complete, and ultimately more defensible, picture of what a company is truly worth.

Alright, let's roll up our sleeves and move from theory to practice. When it comes to figuring out the intrinsic worth of a private business, the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method is where the real work happens. While it’s the most detailed approach for the valuation of a private company, the idea behind it is surprisingly simple: a company’s value today is the sum of all the cash it’s expected to generate in the future, adjusted for the time value of money.

Think of it like buying a small orchard. You're not just paying for the apples you can pick today. You’re buying the right to all the future harvests, too. A DCF analysis is just the financial world's way of figuring out what all those future apple crops are worth in today's dollars. It definitely requires a deep dive into the company's financial engine, but if you break it down into steps, it's far less intimidating.

Any solid DCF analysis is built on three crucial pillars. Get these right, and you'll have a credible valuation. Get them wrong, and the whole thing falls apart.

The biggest hurdle for private companies? A lack of public data. This makes every assumption you make that much more critical, and you have to be ready to defend them.

Your first task is to project the company's financial future. This means building a financial model based on its past performance, what's happening in its industry, and what the management team expects. You’re trying to predict revenue growth, profit margins, and how much the company needs to reinvest to keep growing.

For instance, a booming SaaS startup might forecast 30% annual revenue growth for the next three years, then see that growth cool to a more stable 15% for the following two. These projections are the bedrock of your FCF calculation.

Key Insight: Don't mistake Free Cash Flow for net income. FCF is a much purer measure of economic value because it tracks the actual cash left for investors after all business needs are met, cutting through accounting noise like depreciation.

For private companies, figuring out the discount rate is where the "art" of valuation really comes into play. The go-to formula is the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), which requires inputs like the cost of debt and the cost of equity. The tricky part is the cost of equity, which needs a "beta"—a number that measures a stock's volatility compared to the overall market.

Private companies don't have a stock price, so they don't have a beta you can just look up. So, what's an analyst to do?

This multi-step process helps ensure your discount rate truly reflects the unique risk profile of the business you're valuing.

Finally, you have to put a value on everything that happens after your detailed forecast ends. This is the terminal value, and it represents all cash flows from that point into perpetuity. There are two popular ways to do this:

Once you have the present value of your forecasted cash flows and the present value of your terminal value, you add them together. The result is the company's enterprise value. It's a complex, assumption-heavy process, but it provides the most fundamental and insightful view of what a company is truly worth.

Of course. Here is the rewritten section with a more natural, human-expert tone.

So far, we've focused on looking inward at a company's own financial forecasts. But one of the most powerful ways to figure out what a business is worth is to look outward at what’s happening in the real world. This is what we call the Market Approach, or more commonly, "comps."

The core idea is simple and intuitive. You're asking: What are similar businesses selling for right now?

Think about pricing a house. You wouldn't just guess. You'd look at what similar houses in your neighborhood have recently sold for. Comps for a business work the same way. They provide a reality check that’s grounded not in theoretical spreadsheets but in actual, recent market transactions and what real investors are willing to pay.

There are two main ways to pull this off:

The entire Market Approach lives or dies by the quality of your comparisons. Your goal is to assemble a "peer group" of companies that are genuinely alike. If you pick the wrong peers, your valuation will be miles off. It's that simple.

When you're building this group, you need to look at more than just the industry label. You're looking for true operational and financial twins. Consider these factors to make sure you're comparing apples to apples:

Let’s be honest: finding a perfect public doppelgänger for a private company is next to impossible. The real skill is in finding a reasonable set of comps and being ready to defend your choices, while openly acknowledging the differences.

Once your peer group is set, the next move is to calculate valuation multiples. These are simple ratios that connect a company's total value to a single, critical financial metric. The two most common are EV/Revenue and EV/EBITDA.

Enterprise Value (EV) / Revenue is the multiple of choice for fast-growing companies that often aren't profitable yet—think of most tech startups. Research from SaaS Capital shows that the median public B2B SaaS company trades around 7.0x its current run-rate revenue. But that average hides a massive spread. The absolute best-in-class companies can fetch multiples over 14x, while those struggling might not even hit 2x.

Enterprise Value (EV) / EBITDA is what you'll use for more mature, stable businesses. For these companies, profitability and cash flow are much better indicators of value than just top-line growth.

The art here isn't just in the math, but in picking the right multiple. A revenue multiple tells a story about growth and market hype. An EBITDA multiple tells a story about efficiency and the ability to generate cold, hard cash.

Now for a crucial step. You can't just snatch a multiple from a public company and slap it onto a private one. Private companies come with their own unique quirks that demand major adjustments. The big one is the Discount for Lack of Marketability (DLOM).

Shares in a private company are illiquid. You can't just log into a brokerage account and sell them tomorrow. This lack of a ready market makes them inherently less valuable than their publicly traded cousins. The DLOM is a percentage discount you apply to the valuation to account for this. It can be anywhere from 15% to 30%, sometimes even more, depending on the company's situation.

Let's see how this plays out with a quick example of a tech startup:

Following this process takes the valuation of a private company out of the realm of guesswork and turns it into a disciplined, market-based financial analysis.

Here is the rewritten section, designed to sound like an experienced human expert.

Valuing a private company is never a clean, straightforward calculation. It’s messy. You're constantly dealing with obstacles, debates, and judgment calls that make the process feel more like navigating a maze than following a neat roadmap. The valuation methods give you a framework, but the real work—and the real challenge—is applying them in the real world.

The biggest hurdles are baked into the very nature of private businesses. Unlike public companies that live in a glass house of disclosure, private firms operate behind a curtain. This creates some serious difficulties for anyone trying to pin down a realistic valuation. Knowing these obstacles upfront is the key to setting reasonable expectations and arriving at a number you can actually defend.

Right out of the gate, you’re hit with the information gap. Public companies are legally required to open their books every quarter, publishing mountains of financial data. Private firms? Not so much. This means analysts are often working with patchy or incomplete information, which makes building a solid financial model or finding truly comparable companies a lot harder.

This lack of hard data forces you to rely more heavily on assumptions. Of course, these are always educated guesses based on the best information you can find. Still, they add a layer of subjectivity that you just don't see in public market analysis. Every single projection, from future growth rates to the selection of a peer group, is open for debate.

Another fundamental issue is illiquidity. You can’t just log into your brokerage account and sell shares in a private company with a single click. This lack of marketability makes private stock inherently less valuable than an equivalent, easily traded public stock.

The core problem is that your investment is locked up, often for an unknown amount of time. To account for this risk, valuators have to apply a significant haircut—the Discount for Lack of Marketability (DLOM)—which is a step that requires a ton of professional judgment.

A major trend that’s really complicating things is that companies are staying private for much longer. The median age of a company at its IPO has jumped from 6.9 years a decade ago to 10.7 years today. Why? Because there's a flood of private capital from venture funds and other big investors, letting companies get huge without ever facing the scrutiny of the public markets. You can read more about the growth of private markets and the whole "unicorn" phenomenon.

This trend creates a couple of big valuation headaches:

These issues don't make private valuation impossible, but they highlight why it’s so critical to use multiple methods, document every assumption meticulously, and lean on experienced professional judgment. The final number isn’t just pulled out of a formula; it’s the result of a rigorous process built to handle these inherent complexities.

Running the numbers is just the beginning. The real test is presenting those findings in a report that’s both credible and defensible. Think of it this way: your goal isn’t just to land on a single magic number. It's to build a compelling story that can stand up to tough questions from investors, auditors, or even potential buyers. A great report showcases a transparent, rigorous process.

The most convincing valuations never hang their hat on a single method. Instead, they blend the results from multiple approaches—like DCF, comparable companies, and precedent transactions—to create a valuation range. This triangulation isn't just for show; it demonstrates thoroughness and anchors your final number within a logical framework, minimizing the risk of any one flawed assumption throwing everything off.

Every single assumption you make during the valuation of a private company needs to be written down and justified. Why did you choose that particular group of peer companies? How exactly did you land on your growth rate or discount rate? Clear, detailed documentation is what separates a subjective opinion from a defensible analysis.

It’s just as important to tailor the report for the people who will actually read it. A valuation prepared for your own internal strategic planning will look very different from one designed for IRS tax compliance (like a 409A) or a tense M&A negotiation. The context is king.

The gold standard is a valuation that tells a clear story, supported by evidence at every turn. It should leave no room for doubt about the rigor of the process used to determine the company's worth.

This level of detail is especially critical when markets get choppy. While private equity fundraising cooled off a bit in early 2024, the long-term forecast for private markets is still incredibly strong, with some projections pointing to a market size of nearly $30 trillion by 2033. Unlike public stocks that fluctuate daily, private valuations move more slowly. This offers some stability, but it also means your valuation process has to be rock-solid. You can discover more about the future of private market investing to get a better handle on these dynamics.

Look, understanding valuation is a core skill for any founder or executive. But there are absolutely times when bringing in an independent, third-party expert is a must.

For any formal reason—think tax compliance, shareholder disputes, litigation, or raising money from institutional investors—an external valuation is non-negotiable. It provides the objectivity and credibility that stakeholders require. It sends a clear signal that the number isn't just an optimistic founder's guess, but a fair market assessment backed by professional standards.

Even after you get a handle on the main methods for valuing a business, real-world questions always seem to come up. Let's tackle some of the most frequent ones we hear from founders, investors, and even employees trying to understand what their equity is worth.

As a basic rule of thumb, you should get a formal valuation done at least once a year. This keeps you compliant and helps with internal financial planning.

But more importantly, you absolutely need a fresh valuation before any major financial event. Think of it as a financial health check-up; you need one regularly, but you'd never skip it right before a major life decision.

You'll need a new valuation when you're about to:

A 409A valuation is a very specific appraisal that the IRS requires. Its whole purpose is to establish the fair market value (FMV) of your company’s common stock. Why? It's all about setting a compliant strike price for employee stock options. Getting this right protects both the company and your employees from some seriously nasty tax penalties.

A 409A is a critical piece of the valuation puzzle, but remember what it’s for: tax compliance. The final number might look different from a valuation done for a strategic sale, which could factor in things like a control premium that a 409A wouldn't.

This is a classic "it depends" answer. The cost of a professional valuation can swing wildly based on your company's size, how complicated your business model and cap table are, and why you need the appraisal in the first place.

For a young startup that just needs a standard 409A, you might be looking at a few thousand dollars. But for a larger, more complex business heading into an M&A deal or a legal battle, the fees can easily run into the tens of thousands.

You can—and you should—run your own numbers. Having a solid internal estimate is incredibly useful for strategic planning and understanding your own business. But that back-of-the-napkin calculation is no substitute for a formal report.

Any valuation that needs to hold up for legal, tax, or investment reasons has to be done by an independent, qualified appraiser. That third-party objectivity is what makes the report credible and defensible to the IRS, your investors, and auditors. It’s not a place to cut corners.

For emerging fund managers, getting valuation right is just one part of the job. Fundpilot helps you move beyond messy spreadsheets with institutional-grade reporting, automated fund administration, and built-in compliance tools. See how you can streamline your back office and deliver better insights to your LPs by exploring the Fundpilot platform.