What is a capital call? This guide breaks down the capital call definition, process, and legal framework for investors in private equity and venture capital.

So, what exactly is a capital call? Think of it as a formal "show me the money" moment in the world of private investment. When a fund manager finds a promising investment opportunity, they'll issue a capital call to their investors, asking them to send over a portion of the money they've already agreed to invest. This process, also known as a drawdown, is the engine that powers private equity and venture capital funds. Instead of collecting a massive pile of cash upfront and letting it sit around, managers "call" for capital precisely when it's needed.

Let's use a simple analogy. Imagine you've hired a top-tier general contractor to build your dream home, and you've both agreed on a total budget of $1 million. You wouldn't just hand over a check for the full amount on the first day, right? Of course not. Instead, the contractor requests funds as they hit key milestones—$100,000 to pour the foundation, another $50,000 for framing lumber, and so on. A capital call operates on this very same "just-in-time" principle.

Let's use a simple analogy. Imagine you've hired a top-tier general contractor to build your dream home, and you've both agreed on a total budget of $1 million. You wouldn't just hand over a check for the full amount on the first day, right? Of course not. Instead, the contractor requests funds as they hit key milestones—$100,000 to pour the foundation, another $50,000 for framing lumber, and so on. A capital call operates on this very same "just-in-time" principle.

In the fund world, investors are called Limited Partners (LPs). They make a total pledge to the fund, say $5 million over its entire lifespan. This is their committed capital. The fund manager, known as the General Partner (GP), doesn't take all that money at once.

To truly grasp how capital calls work, you need to know the difference between two fundamental concepts.

Before we dive deeper, let's get the key terms straight. This table breaks down the essential vocabulary you'll see again and again.

| Term | Simple Explanation |

|---|---|

| Committed Capital | The total amount an investor has legally promised to contribute to the fund over its lifetime. It's the full IOU. |

| Paid-In Capital | The actual cash an investor has sent to the fund to date in response to one or more capital calls. It's the money that's been put to work. |

| Limited Partner (LP) | An investor in the fund. They provide the capital but are not involved in the fund's day-to-day management. |

| General Partner (GP) | The fund manager. They find investment opportunities, manage the portfolio, and issue capital calls. |

Understanding these terms is the first step. The capital call is simply the bridge that turns a promise (Committed Capital) into action (Paid-In Capital).

So, when the GP finds a fantastic opportunity—like acquiring a fast-growing tech startup—they send a formal notice to their LPs. This notice requests the specific amount of cash needed to close the deal. This method is incredibly efficient. It avoids having millions of dollars of investor money sitting idle in a low-interest bank account, a problem known as "cash drag" that can seriously hurt a fund's overall performance.

A capital call isn't an unexpected bill; it's a planned, legally-binding step in a long-term investment strategy. It ensures capital is deployed at the precise moment an opportunity arises, maximizing efficiency and potential returns for everyone involved.

By getting comfortable with this rhythm, investors can better appreciate how private funds operate. For a more detailed look, you can learn more by understanding the capital call definition in our complete guide. This model truly frames the capital call not as a burden, but as a strategic tool for smart, just-in-time funding.

So, what does a capital call look like in the real world? It's not some surprise event that pops up out of nowhere. It's a well-defined process that really starts the moment a fund manager—the General Partner (GP)—spots a great investment opportunity.

From an investor’s point of view, the whole thing is designed to be straightforward. Once the GP decides to pull the trigger on a deal, they kick off a formal, structured procedure. This isn't just a casual "hey, we need some money" phone call; it's all governed by the legal agreements you signed when you joined the fund.

The first tangible step for you as an investor (or Limited Partner) is getting a capital call notice. This is a formal, legally binding document. You can think of it as the official invoice for your portion of the fund's next big move.

This notice is packed with critical information—no vague language allowed. It will clearly spell out:

This window gives you enough time to get your affairs in order and move the cash from your liquid accounts to the fund's specified bank account. The notice will include clear wiring instructions to make the transfer as smooth as possible.

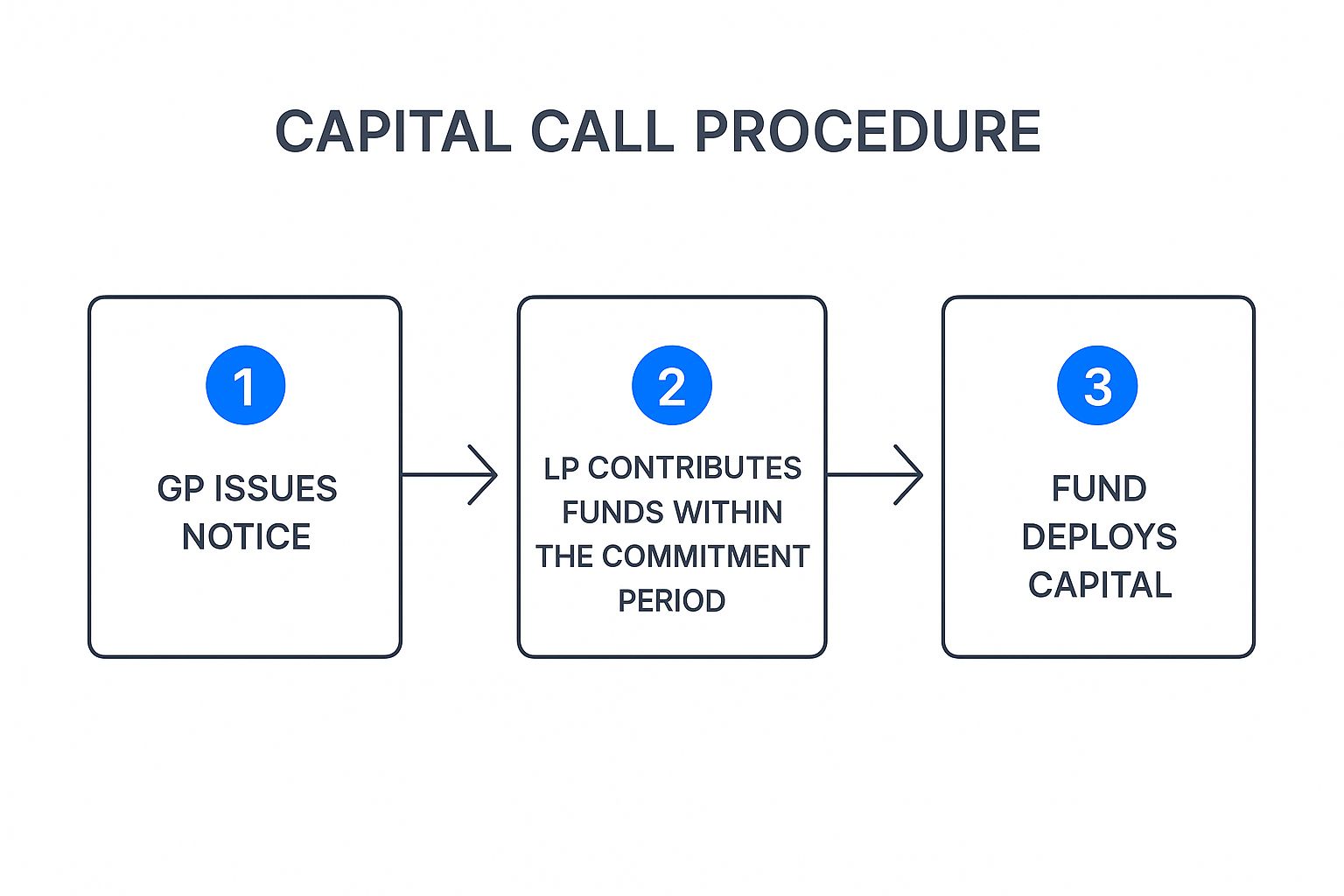

This simple, three-step flow is really all there is to it.

As you can see, the process moves logically from the GP's request to the investor's contribution, and finally to the fund deploying that capital.

Once all the LPs have wired their share, the GP aggregates the funds and closes the investment. It’s a transparent and efficient operation that ensures everyone's money is collected for a clear, stated purpose—which is the entire point of a capital call.

When a fund manager issues a capital call, it’s not just a casual ask for money. It's a legally binding obligation, and the entire process rests on a critical document: the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA).

Think of the LPA as the master rulebook for the fund. It's meticulously negotiated and signed by everyone before a single dollar is invested, acting as the bedrock of the relationship between investors (Limited Partners) and the fund manager (the General Partner).

This agreement protects both sides of the table. For the fund manager, it grants the legal authority to call capital when a promising investment arises. For you, the investor, it provides clarity, predictability, and a powerful shield against any unwelcome surprises down the road.

The LPA is what gives a capital call its legal weight. It lays out the exact terms of engagement in black and white, leaving no room for guesswork. This document is the cornerstone that makes the entire fund structure possible, offering a clear framework for how business gets done. As Moonfare.com notes, the LPA is what brings clarity to the investment process itself.

Specifically, the LPA will always spell out a few key components:

Understanding the LPA is just as important as the initial decision to invest. It transforms a handshake agreement into an enforceable contract that dictates how and when your capital is put to work.

A thorough review of the LPA is a non-negotiable step in your investment journey. To learn more about what this involves, take a look at our complete guide on what is the due diligence process.

So, why don't fund managers just take all your committed capital on day one? It seems simpler, right? The answer boils down to a core strategic principle in investing: the concept of "dry powder."

Think of it this way: a fund manager is like a master strategist. They wouldn't send all their best troops into a minor skirmish right at the start of a campaign. Instead, they keep their elite forces in reserve, ready to deploy at the most decisive moment. That reserve is the dry powder—the uncalled portion of your capital commitment.

If a fund collected 100% of the money upfront, most of it would just sit in a low-yield bank account while the manager hunted for the right deals. This creates a huge problem known as "cash drag," which erodes the fund's overall performance. Your money would be earning next to nothing instead of being put to work effectively.

By leaving the capital with you, the Limited Partner (LP), until it's actually needed, fund managers ensure that money stays productive in your own accounts. This “just-in-time” funding is what makes the capital call model so smart.

This practice is the lifeblood of private equity. That pool of uncalled capital, or dry powder, is the fund's firepower. It’s what allows them to jump on great opportunities as they arise. Recent years have seen a massive buildup of this available capital, giving fund managers incredible flexibility. If you want to dive deeper, you can discover more insights about dry powder management on allvuesystems.com. This approach guarantees your money is only called when it can be put to immediate use.

A capital call isn't just an administrative task for collecting money. It’s a sophisticated tool for financial timing, turning investor capital from a static pile of cash into a dynamic, opportunistic asset.

Ultimately, this structure is a win-win. It gives the fund manager the agility to act decisively on promising deals while making sure your capital isn't sitting idle and diluting your potential returns. It’s a finely tuned balance between being ready to pounce and maximizing value over the long haul.

In the world of high-stakes investing, speed is everything. When a hot deal comes across your desk, you can't afford to wait around. The standard 10 business days it takes for capital call funds to land in the bank can feel like an eternity, often long enough to see a prime opportunity slip away to a nimbler competitor.

This is where a powerful tool called a capital call facility—often called a subscription line of credit—comes into play.

Think of it as a short-term bridge loan for the fund itself. Instead of waiting for investors to wire their money, the fund can borrow against its Limited Partners' legally binding commitments. This gives the fund manager immediate access to cash, ready to deploy at a moment's notice.

With a subscription line in place, a fund manager can jump on a deal and close it almost instantly. The paperwork gets signed, the asset is secured, and then the manager issues the formal capital call to the LPs. Once those investor funds arrive, they're simply used to pay back the short-term loan.

This completely changes the game. It gives managers the confidence and agility to act decisively on time-sensitive opportunities, ensuring they can lock down the best possible assets for their portfolio.

It’s no surprise that capital call facilities have become an indispensable part of modern private equity. They are critical for speeding up the investment cycle, allowing fund managers to operate at the pace of the market, not the pace of bank transfers. For a deeper dive, you can read more about how these facilities work in private equity.

By using subscription lines, a fund can move at the speed of the market. This isn't just a matter of convenience; it's a real strategic edge that directly benefits investors by ensuring the fund can compete for—and win—the most promising deals.

Ultimately, this mechanism closes the gap between finding a great opportunity and actually funding it. It makes the entire investment process more efficient and effective for everyone involved.

Even with a clear grasp of what a capital call is, real-world situations always bring up more questions for both investors and fund managers. Getting comfortable with the details is key to navigating the private investment world with confidence. Let's tackle some of the most common "what ifs" and "how oftens" to clear up any confusion.

The goal here is to move past the textbook definition and get into the practical side of things, making sure you're ready for what happens at every stage of a fund's life.

This is a big one. When an investor fails to send their money after a capital call, it’s not just a minor slip-up; it's a default. This is a serious violation of the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA), which is the legally binding contract for the fund. The fund manager has a duty to the other investors to enforce the penalties laid out in that agreement.

While the specifics can differ from fund to fund, the consequences are always severe. They’re designed to be. A defaulting investor might face:

There’s no set calendar for capital calls. The timing is completely tied to the fund's deal flow. Put simply, calls happen when the General Partner (GP) finds a promising investment and needs the cash to close the deal.

You can generally expect more activity in the first 1-3 years of a fund's life. This is the "investment period" when the GP is busy putting the money to work and building out the portfolio. After that initial stretch, calls usually become less frequent, often reserved for follow-on investments in companies already in the portfolio or for covering the fund's operating expenses.

Absolutely not. A fund can never call for more capital than the total amount you signed up for in the Limited Partnership Agreement. That number—your committed capital—is the hard ceiling on your financial obligation.

A capital call is just the tool used to draw down the money you've already pledged. It is never a way to increase that pledge. The fund's entire legal and regulatory standing depends on sticking to these agreed-upon limits.

However, it's worth noting that some LPAs have clauses for "recycling" capital. This means if an investment is sold early for a profit, the fund can call that same money again for a new deal. Even with recycling, your total cash paid into the fund will never go over your original commitment. This is especially important for fund managers under specific regulations, like exempt reporting advisers, who have to follow strict compliance rules. You can dive deeper into this by reading this key compliance guide for exempt reporting advisers.

Juggling capital calls, keeping LPs in the loop, and staying compliant is a lot of work. Fundpilot gives emerging fund managers the power to automate these crucial back-office tasks. This frees you up to focus on what you do best: finding great deals and raising capital. Upgrade from manual spreadsheets to an institutional-grade platform with Fundpilot.